My first job out of college was selling office equipment. The first thing I ever learned about selling (from my very Southern sales manger) was that “Telling ain’t selling.” In layman terms, stop telling customers why they need your product and start listening to their needs.

For years this simple phase remained in my memory. It guided me as a way to engage prospects in advisory-like sales dialogue, probing for a need to sell to. But, after attending CEB’s Sales & Marketing Summit last week, where new research highlighted the increased complexity in reaching a purchase decision, I’m now considering rethinking my whole approach.

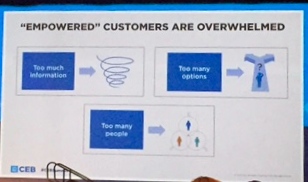

Why? Because buyers have become overwhelmed by the potential choices,  and the involvement of other decision makers in the process, according to Brent Adamson, co-author of The Challenger Customer. Too much information, too many options and too many people involved in the process are making it more difficult than ever to reach a consensus, let alone a purchase decision. Given the complexity, stalled deals are no longer a sales issue; they’re a buying problem.

and the involvement of other decision makers in the process, according to Brent Adamson, co-author of The Challenger Customer. Too much information, too many options and too many people involved in the process are making it more difficult than ever to reach a consensus, let alone a purchase decision. Given the complexity, stalled deals are no longer a sales issue; they’re a buying problem.

The question is: Are marketers contributing to that problem? Is it possible our content marketing efforts, aimed at helping buyers make an informed choice, are becoming part of the “too much” problem? According to Psychologist Barry Schwartz, author of The Paradox of Choice, too much choice often results in no choice at all.

Dr. Schwartz’s research has shown that limiting choice is often necessary to reach a decision, and/or to speed up the buying process. As he said, “When you make choice easier, or more simple, you will sell more.”

For business-to-business sales and marketers, the key is to become “prescriptive,” according to Adamson. Customers need a “trusted advisor” to help guide them through the complexity of the decision making process, in particular in driving a consistent point of view on the problem, and the best solution. Schwartz suggests focusing on the following three areas:

- Be the “expert” or “simplifier.” Help reduce the complexity of the problem, process and/or solution. Smart content should help to explain and simplify solutions to complex problems.

- Create an “anchor.” Help customers understand how to assess the value you offer. Buyers may have a hard time assessing the true value of a new purchase or a new vendor. Help them by giving them context. Find a relatable anchor comparison. Think: ”Platinum service at a standard price.”

- Understand the impact of “no decision.” If no decision is the right decision, then find a way to make it the default answer. This approach is commonly seen in software or subscription-based services where membership/licensing automatically renews.

Do we now dictate to customers/prospects? Not according to Schwartz. Asking probing questions that lead customers to convince themselves that they need your product is the path to goal attainment. Help them understand how your product/service uniquely solves their problem by guiding their path to purchase.

The words of wisdom given to me years ago were right, but given today’s increased complexity it needs an updated “Telling ain’t selling…until it is.”